Contents

- B.C. Home

Quick access to information based on government's structure

British Columbia’s current water allocation system clearly defines access to water in an orderly and predictable way, which has facilitated settlement, agriculture, and economic development. However, it was designed for a time when water shortages were uncommon. Pressures have changed, and like elsewhere, weaknesses have emerged. The system needs to be more efficient, flexible, and capable of adapting to changing conditions, particularly as pressures on water supplies intensify and supply patterns change. Challenges of the “first in time, first in right” principle in the Water Act are shared by many jurisdictions that have used this model. Modifications could range from small incremental modifications to major shifts.

Users and businesses want to know how secure their water supply is. They want to understand their responsibilities and feel confident that their business practices are sustainable and do not harm the environment. Clearly defined and stable allocation rules and processes that provide for ecosystem protection and certainty of access will achieve this.

Flexibility enables proactive responses to conflict or ecosystem risk and is important when managing a resource in a changing climate. Flexibility in the Water Act can help our decision makers to respond quickly in the areas where new information and science shows that changes are needed.

Water allocation systems have broad and important ramifications. The Water Act establishes that the provincial government is the “owner” of the water. Rights to use the water (but not own) are established under licences or approvals issued under the Act.

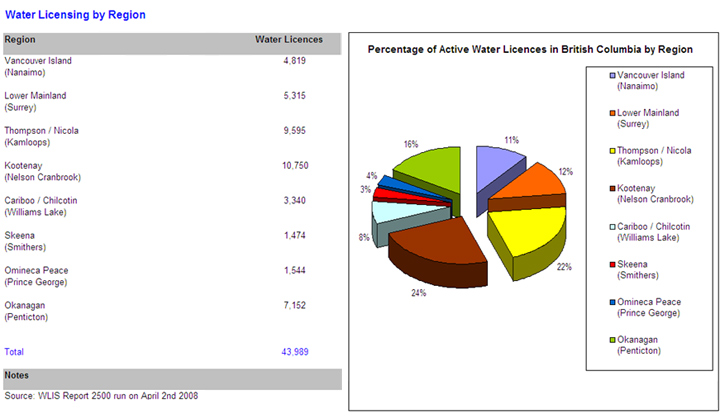

B.C. has been allocating water in perpetuity for more than a century and there are few incentives for water users to be efficient. It is argued that this practice contributes to B.C. being one of the largest per capita water users in the world. In British Columbia there are about 44,000 water licences authorizing the diversion, use, and storage of water. Licences are granted according to the doctrine of “first in time, first in right” (or FITFIR). This means applications are dealt with one at a time and the date of the application establishes the priority date of the licence. The purpose for which the water is used has no bearing on its priority (short term use approvals do not have a priority date). When water is scarce, the rights of “senior” licensees (i.e., those holding licences with earlier priority dates) take precedence over “junior” licensees.

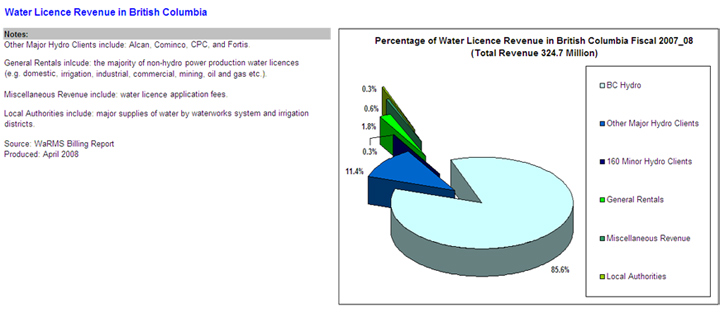

For a ‘power’ purpose, the term of a licence is set at forty years. For a purpose other than power, a licence usually has no expiry date although there is authority to attach a term. The licence or approval does not imply that the quality of the water is suitable (or will remain suitable) for the intended purpose. Licensees pay an annual rental fee for the water they are entitled to use.

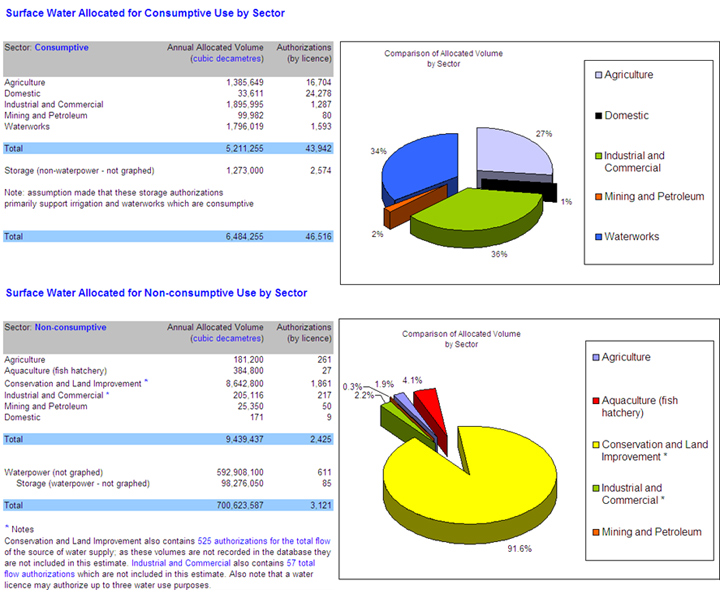

The following graphs provide further detail about major rivers and watersheds in BC and the way water is allocated across the province:

Distribution of Major Rivers and Watersheds in BC

Source: ILMB Land Resource Data Warehouse. Produced: May 2008

Source: ILMB Land Resource Data Warehouse. Produced: May 2008 Table of Drainage of Major Rivers

| River | Drainage area (km2) | Length (km) | Average Annual Discharge (m3/sec) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fraser | 231,312 | 1,368.5 | 3,600 |

| Liard | 143,418 | 483.0 | 1,300 |

| Peace | 128,451 | 281.7 | 1,400 |

| Columbia | 103,004 | 750.3 | 2,800 |

| Skeena | 54,488 | 579.6 | 1,000 |

| Stikine | 50,362 | 539.3 | 1,000 |

| Nass | 20,839 | 378.3 | 900 |

| Source: McGillivray, B. Geography of British Columbia: People and Landscapes in Transition, UBC Press 2000 | |||

British Columbia is not alone in modernizing its water legislation – many countries have done so since the 1990’s to address increasing challenges that could not readily be accommodated under existing statutes.

Some jurisdictions (e.g., United States) have made changes incrementally, resulting in complex legislation. Others have repealed and replaced their legislation resulting in wholesale changes all at once (e.g., South Africa). Yet others are involved in a “supra-national” initiative (e.g., the European Union’s Water Framework Directive) in which over-arching objectives for all member nations are established and then each country determines its own particular legislative scheme to comply with the initiative.

In many cases, jurisdictions have employed the use of Economic Instruments (EIs) to improve water efficiency and encourage conservation measures. EIs include subsidies (e.g., interest-free loans to encourage investment in efficient irrigation systems), pricing (e.g., differential pricing to encourage water use efficiency), rebates (e.g., for water conservation), as well as water markets and water trading.

Economic instruments provide a means of incentive for conservation and are considered to facilitate more efficient water allocation.

A discussion paper and supporting technical report that provides more information about water allocation processes will be available online shortly. We encourage you to check this site regularly for updates throughout the Water Act Modernization process and to submit your thoughts and comments via the Living Water Smart blog.

Other sources of information include:

Brandes, Oliver M., Nowlan, Linda, and Paris, Katie. 2008 Going With the Flow? Evolving Water Allocations and the Potential and Limits of Water Markets in Canada. Prepared for the Conference Board of Canada.

de Loë, Rob. 2007. Allocation Efficiency in the Context of Water Security – Discussion Paper for The Science-Policy Interface: Water and Climate Change, and the Energy-Water Nexus, Washington, DC

Final Report: Water Allocation and Water Security in Canada: Initiating a Policy Dialogue for the 21st Century.

Guelph Water Management Group. 2007. Characterization of Water Allocation Systems in Canada. Technical Report 1. Prepared for the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation. Guelph, ON: Guelph Water Management Group, University of Guelph.

Water allocation means the system of rules and procedures that grants access to water through the granting of a licence or approval. The licence or approval provides the holder legal authority to divert and use surface water and can place conditions on the user like fees or monitoring.

Water allocation means the system of rules and procedures that grants access to water through the granting of a licence or approval. The licence or approval provides the holder legal authority to divert and use surface water and can place conditions on the user like fees or monitoring. Leading thoughts and practices are described here for the purpose of providing British Columbians with an understanding of the types of systems and processes adopted in other jurisdictions to allocate water resources. The ideas expressed here are not necessarily those endorsed by the British Columbia Provincial Government.

Leading thoughts and practices are described here for the purpose of providing British Columbians with an understanding of the types of systems and processes adopted in other jurisdictions to allocate water resources. The ideas expressed here are not necessarily those endorsed by the British Columbia Provincial Government.